Key Takeaways

-

Your preparer needs your e-file authorization in hand to file today.

-

How to paper file, if you must.

-

3rd quarter estimates: beware address change.

-

Why high-level IRS people are leaving.

-

The road to shutdown.

-

Always be filing.

-

National Double Cheeseburger Day.

Today marks the extended due date for calendar-year 2024 returns for passthrough entities—partnerships and S corporations. Missing this deadline triggers penalties starting at $245 per Schedule K-1 filed late. For example, a return with 10 K-1s filed one day late incurs a penalty of $2,450. This penalty repeats monthly until the return is filed.

Electronic filing remains the most reliable method to ensure timely submission. Your preparer needs to have your signed e-file authorizations in hand to submit your returns. Your word that you have mailed them isn't enough.

If filing by paper, use certified mail with return receipt requested to avoid penalties, provided the postmark is dated today. Keep the certified mail postmark somewhere safe.

If you fail to get your paper returns to the post office before closing time, you can file timely via designated private delivery services if the package ships today. Be sure to select a qualified service—for instance, UPS Next Day Air qualifies, but UPS Ground does not. Be sure to use to the correct IRS service center street address, as FedEx, UPS and other private services cannot deliver to the IRS post office boxes. Retain your shipping documents to prove that you filed on time.

2025 Federal Estimated Taxes for the third quarter are also due today. Electronic payment is the surest and most secure way to pay. If you insist on using the postal service, double check the mailing address you are using, as the IRS has switched up the mailing addresses since the June second quarter payments were due.

Disaster area filers are eligible for extra time for tax returns and payments. Among the areas eligible for relief:

- California — Los Angeles County: Deadlines on or after Jan. 7, 2025, and before Oct. 15, 2025 are postponed to Oct. 15, 2025. (Includes 2025 estimated payments due Apr. 15, Jun. 16, and Sept. 15.)

- Oklahoma (wildfires and straight‑line winds): Deadlines on or after Mar. 14, 2025, and before Nov. 3, 2025 are postponed to Nov. 3, 2025. (Includes 2025 estimated payments due Apr. 15, Jun. 16, and Sept. 15.)

- Texas — designated counties (severe storms, straight‑line winds, flooding): Deadlines on or after July 2, 2025, and before Feb. 2, 2026 are postponed to Feb. 2, 2026. (Includes the Sept. 15, 2025 and Jan. 15, 2026 estimated payments.)

Check the IRS Disaster relief page for complete details on affected areas and available relief.

IRS on Flaky Tribal Credits; Staff Departures and What They Mean For Taxpayers Under Exam

IRS Tells Employees to Disallow ‘Non-Valid’ Tribal Credits - Erin Schilling, Bloomberg ($):

The IRS published the updates while Billy Long, President Donald Trump’s appointee, was IRS commissioner. Long began at the agency in late June but lasted only two months before being pushed out.

Long found potential buyers for the credits while in the private sector before he was confirmed as commissioner, and he received campaign donations from those associated with the arrangement. Long said during his confirmation hearing he didn’t realize there were any issues with tribal credits and would cooperate with any investigations into the credits.

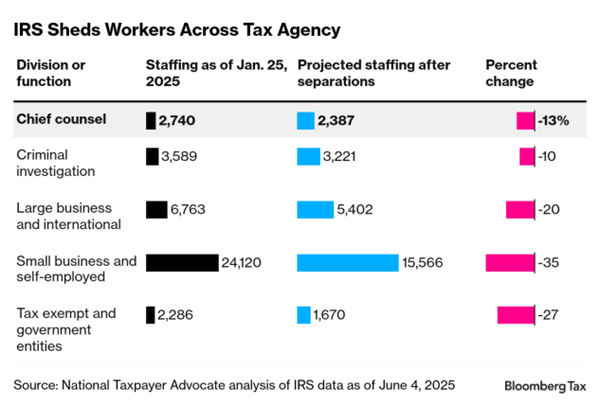

Long Commutes, Fear of the Future: What Made IRS Attorneys Quit - Michael Rapoport, Bloomberg ($):

When IRS attorneys put those together with fear of what the future might hold—that sooner or later they’d be required to do something they couldn’t accept—it was enough to make some head for the door.

IRS Attorney Exodus Gives Companies a Leg Up in Court Cases - Michael Rapoport, Bloomberg ($):

The likely upshot, the former officials and attorneys say: Prolonged uncertainty over disputed tax bills, for both taxpayers and the IRS; resolutions of some cases on terms less favorable to the IRS; and an erosion of the government’s ability to crack down on tax abuses.

Related: Eide Bailly IRS Dispute Resolution and Collections Services

Congress and the Road To Shutdown

As Congress approaches a shutdown showdown, you want to be sure to catch our Quarterly Legislative Update this coming Wednesday at Noon Central Time. Alex Parker will cover recent updates, the state of the showdown, and the possibilities for additional tax legislation this year. No charge, 1 hour CPE available. Register here.

How we’re thinking about this massive week - Jake Sherman, Andrew Desiderio, John Bresnahan and Ally Mutnick, Punchbowl News. "We’re officially in the danger zone. A shutdown appears more likely than not at this point. That’s not to say it’s guaranteed. Shutdowns are terrible politics and policy. But Republicans and Democrats are heading in diametrically different directions right now, with each side comfortably betting on their own strategy. And that could lead to a shutdown unless something changes."

Capitol Hill Recap: Affordable Care Act Credits in the Shutdown Mix - Alex Parker, Eide Bailly. "There’s already been one tense showdown this year over government funding, and Washington is bracing for another one that could go down to the last minute—if they’re lucky."

Shutdown Showdown - Politico Playbook:

But but but: Any funding deal would need GOP-wide support, plus the votes of a number of Dems. And the row about tying in an extension to Obamacare tax credits isn’t going away — with several Republicans warming to the idea. “Among all the troublemaking members House Republican leaders have to deal with, Rep. Jen Kiggans (R-Va.) isn’t on their list of problem children. That might be changing,” POLITICO’s Benjamin Guggenheim and Meredith write this morning.

Millions face skyrocketing health insurance costs unless Congress extends subsidies - Mary Clare Jalonick and Amanda Seitz, Associated Press:

With expiration now just a few months away, some of those people have already gotten notices that their premiums — the monthly fee paid for insurance coverage — are poised to spike next year. Insurers have sent out notices in nearly every state, with some proposing premium increases of as much as 50 percent.

Biden’s COVID Credits Are an ObamaCare Expansion That Congress Should Allow To Expire - Brian Blase and Trevor Carlsen, Paragon Health Institute. "Even after the COVID credits expire, subsidies remain very generous under ObamaCare’s original design. Taxpayers will continue to pay the vast majority of premiums for most enrollees, particularly those with incomes below 250 percent FPL—who make up nearly three-quarters of the exchange population."

OBBBA: New Return Schedules, Errors, and Items That Were Left Out.

IRS Unveils New Draft Schedule for OBBBA Deductions - Mary Katherine Browne, Tax Notes ($):

The draft of Schedule 1-A, “Additional Deductions,” released September 8 allows taxpayers to claim limited deductions for qualified tips, overtime pay, and car loan interest, as well as a new deduction for seniors. Instructions weren’t included with the draft form.

Dem Taxwriters Insist OBBBA Didn’t Kill Home Efficiency Credit - Cady Stanton, Tax Notes ($): "The lawmakers said the bill modifies an incorrect subsection of the tax code when attempting to set an end date for the credit by referencing an end date for the product identification number requirement for the credit rather than amending the subsection on the credit’s termination date."

Related: The Impact of New Tax Legislation on Energy Efficiency Incentives

A List of Tax Provisions Left Out of the Big Beautiful Bill - Andrew Lautz, Bipartisan Policy Center: "As expansive as Congress made OBBB’s tax title, several provisions were ultimately trimmed down or left on the cutting room floor when the bill moved from the House to the Senate and was finalized in late June. Below, BPC reviews these provisions and their budgetary impact (all via the Joint Committee on Taxation)."

This is important work. Many taxpayers have misunderstandings of the bill based on early versions that were changed before final passage.

Tariffs and Unintended Consequences

How the Trump tariffs boomerang to hurt U.S. winemakers - Kevin Williamson, Washington Post:

What tariffs mainly accomplish, then, is to distort markets, disrupt supply chains and increase costs for businesses and consumers. And because the Trump administration changes its tariff targets from day-to-day — or even from hour-to-hour — it introduces more uncertainty into the marketplace, which is a problem for any business but an enormous problem for a business with a product-development cycle measured in decades.

US companies put brakes on hiring after Donald Trump’s tariffs hit - Myles McCormick, Jamie Smyth, and Zehra Munir, Financial Times. "'These tariffs are just a drain on American manufacturers like mine. There’s no benefit. It’s an abrupt tax that is impeding our ability to hire and grow,' said Julie Robbins, chief executive of EarthQuaker Devices, a manufacturer of guitar pedals in Akron, Ohio."

Blogs and Bits

Social media tax scammers have cost duped taxpayers $162 million in IRS penalties - Kay Bell, Don't Mess With Taxes. "The Internal Revenue Service recently issued an alert about a growing number of fraudulent tax schemes circulating on social media. The popular ones right now, according to the IRS, promote the misuse of tax credits such as the Fuel Tax Credit and the Sick and Family Leave Credit."

Advisers Found to Owe Treble Damages to Impacted Taxpayers - Ed Zollars, Current Federal Tax Developments. "CPAs and EAs, even if not directly involved in a tax structure, face risk if they fail to strongly advise clients to obtain information about proposed transactions, the relationships of partners, and to raise concerns when promoters suggest inflated qualified appraisals. While clients may be swayed by potential tax benefits, advisors must ground them by highlighting the apparent absurdity of such transactions."

How to Shrink—or Even Eliminate—Capital Gains on Your Home Sale - Robyn Friedman, Wall Street Journal. "Dennis said that one of the most common ways homeowners can reduce taxes on the sale of their primary residence is the exclusion authorized by the Internal Revenue Code that allows single taxpayers to exclude $250,000 of gain and married taxpayers who file jointly to exclude $500,000."

Keep On Filing

Florida Businessman Charged with Tax Evasion - U.S. Department of Justices (Defendant name omitted, emphasis added):

The indictment further alleges that, after Defendant received letters from the IRS in 2019, he hired a tax attorney and return preparers and told them a false story: that over $3.8 million in dividends that he received between 2013 and 2018 were nontaxable loans. Defendant allegedly also falsely told these professionals that he did not know the other shareholders of the business. As a result of these falsehoods, the tax professionals allegedly drafted tax returns for Defendant for 2013 through 2020 that underreported his income and taxes due. Except for the 2013 return, all these false tax returns were allegedly filed with the IRS.

Longtime readers may notice how the defendant got in trouble, should the allegations prove true. Not filing is a great way to get the IRS to notice you. That's especially true if you've been filing regularly and your income has gone up by a lot. There are almost always information returns with your name on them, and even the old IRS computers notice when there is no return to match the 1099s.

The government says that rather than coming clean when the IRS started sending notices, the defendant made up false stories to explain the income and hired professionals to file returns based on the lies. You don't get to blame preparers if you don't tell them the truth.

The moral? Keep filing, report your income, and be square with your tax pros.

What day is it?

It's not just a filing deadline. It's National Double Cheeseburger Day! Reward yourself for timely filing with a comforting and tasty pile of beef and cheese!

Make a habit of sustained success.